Introduction

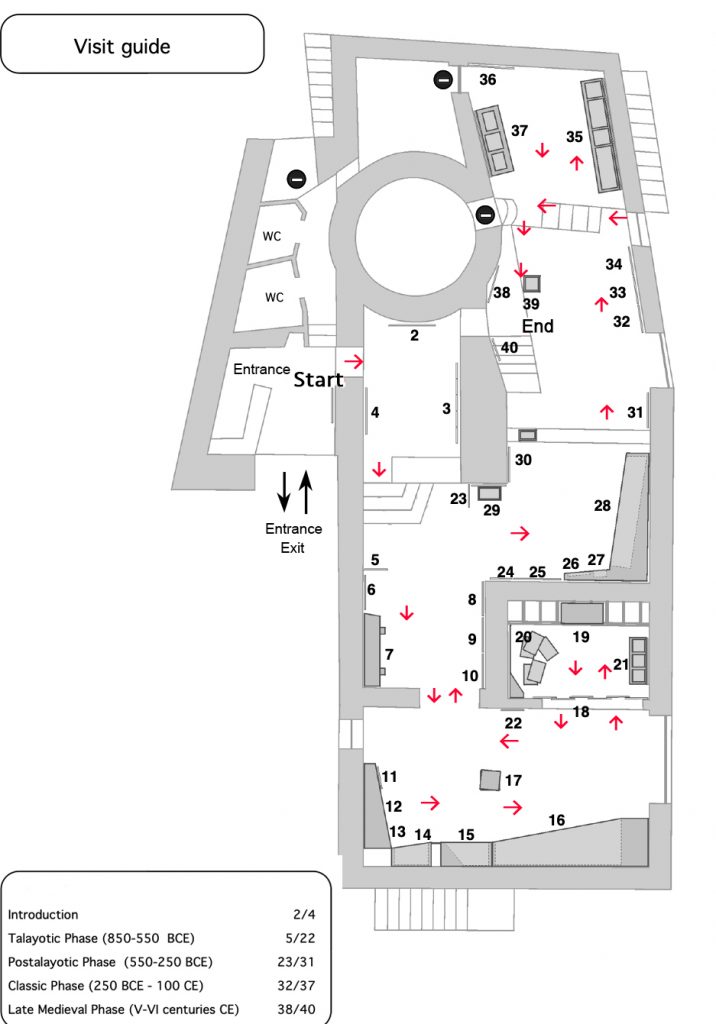

2. Son Fornés in its surroundings

The Balearic Islands were uninhabited until about 4500 years ago, when the first settlers arrived in Mallorca. Throughout prehistory, the Balearic communities developed highly original forms of social organization, without losing contact with neighbouring societies. As time went by, the sea became less of an obstacle to travel. As a result, the Balearic Islands lost much of their autonomy, and instead came to play an almost entirely secondary role in larger political and economic units. Mallorca is the fourth largest island in the Western Mediterranean, with a surface area of 3,640 km2. It has a very varied topography, which mountain ranges of more than 1,000m in altitude, interior valleys, and coastal plains.

This broken landscape causes differences in rainfall patterns, which vary between 350 and 1,400 mm annually, as well as in temperatures, and vegetation. The present day population is about 900,000 inhabitants, although the great attraction of Mallorca for tourists means that in summer this figure is increased up to much as 10 times.

The municipality of Montuïri is rich in archaeological sites. Most of them have been discovered by accident, and, unfortunately, some have suffered serious damage. Nevertheless, they give us the chance to understand our past, and they represent a collective heritage which must be preserved for future generations.

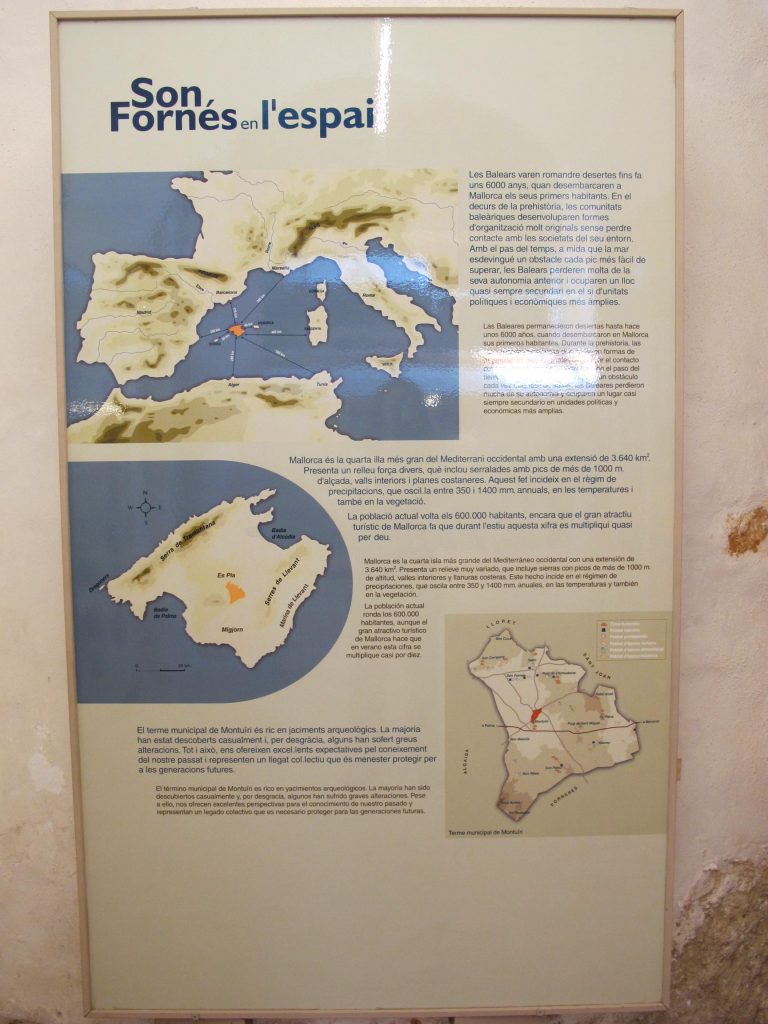

3. Chronological Framework

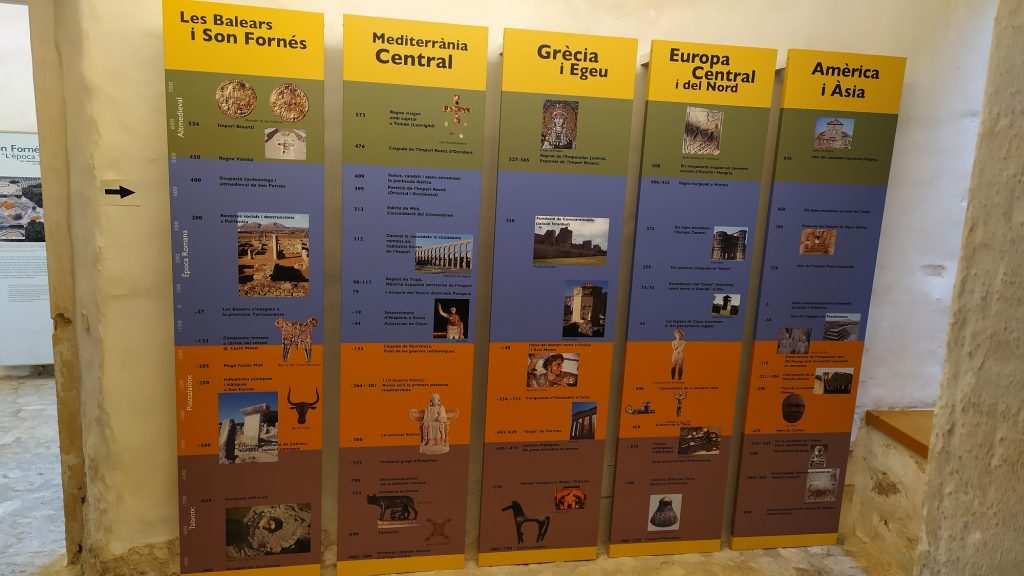

4. History of the research in Son Fornés

Son Fornés is a key site for understanding Mallorca’s ancient society and history. Excavations began in 1975 under Vicenç Lull’s lead, who succeeded in creating a research group that grew larger over time and remains attached to the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Mediterranean Social Archaeoecology Research Group / ASOME-UAB).

The Museum integrates all field and lab research from the site and oversees conservation and restauration works.

Talayotic Phase: 850 – 550 BCE (before Christian Era)

5. The Talayotic Phase. A meeting among 2,000 tonnes of stone (banner)

6. Cyclops of stone

Talayots are the most familiar, and at the same time the most mysterious monuments in the Balearic Islands. Their abundance, imposing appearance, and mysterious origins have stimulated popular and specialist interest for centuries. Many things have been said about these huge structures: “towers (atalayas = talayots) from Moorish times”, pagan temples, tombs of kings, or residences of giants. The development of archaeological studies from the early years of the 20th century has helped us to understand our past better, but the talayots continue to hide their secrets from us. Josep Sanz, the village schoolteacher of Montuiri in the middle of the 20th century, hardly imagined that those almost invisible ruins, among which retaught the history of Mallorca, would give us many of the answers to the enigma of the talayots. Thanks in large part to his interest in culture and his perseverance, the Son Fornés archaeological research project was born in 1975. Its aim was to discover the functions of these structures, and to understand the society which constructed them. As well as its central position in the island, Son Fornés also occupies a fundamental place in the panorama of Mallorcan archaeology, since it continues to be the island’s best known talayotic site. Among its findings are the largest and best preserved talayot of Mallorca (Talayot nº 1), and a wide range of remains of housing and utensils, which give us an idea of the social life of the prehistoric inhabitants of the island. Even so, there are aspects which remain to be discovered. The research continues, and, without doubt, we can expect new and interesting discoveries.

7. Son Fornés: a Talayotic settlement, c. 850-550 BCE: (computer multimedia)

8. Contemporary societies

Talayotic society was contemporaneous with the development of many state formations in the Mediterranean basin, and of long distance exchange networks, favoured in part by Phoenician and Greek colonial and commercial expansion. However, the Balearic Islands remained very much at the margin of this broad panorama of changes, and limited their contacts to trade in metals (tin and probably copper), with Central and Northeast Europe.

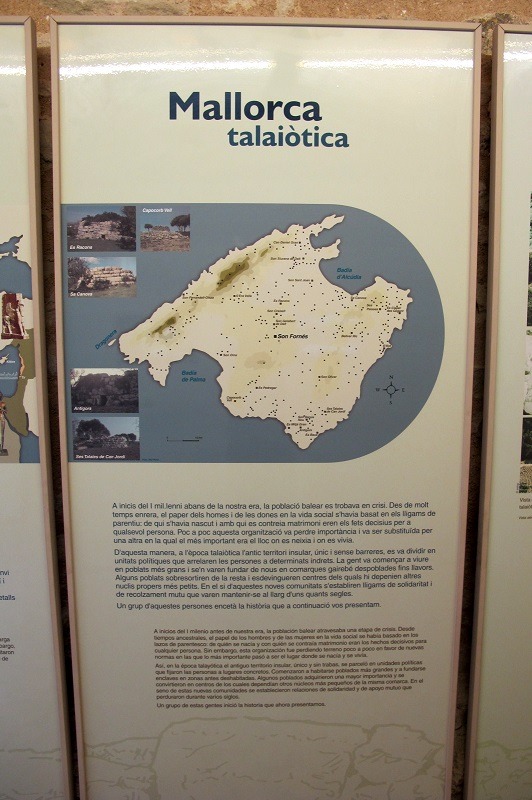

9. Talayotic Mallorca

At the beginnings of the 1st millennium BCE, the Balearic population was undergoing through a period of crisis. From ancestral times, the role of men and women in social life had been based on kinship: parents and couples for marriages were the major facts that determined social identity. However, this organizational system began to give way to new norms in which the most important facts were the place where someone was born and the one where he or she lived. Thus, in the Talayotic Period, the old island territory, undivided and unshackled, was parceled into political units which fixed people to concrete places. Larger settlements began to appear, and enclaves were founded in previously uninhabited areas. Some settlements acquired a greater importance, and became centers, with other, smaller settlements depending on them. At the heart of these new communities, relations of solidarity and mutual support were established, which endured for several centuries. A group of these people began the story which we are now presenting.

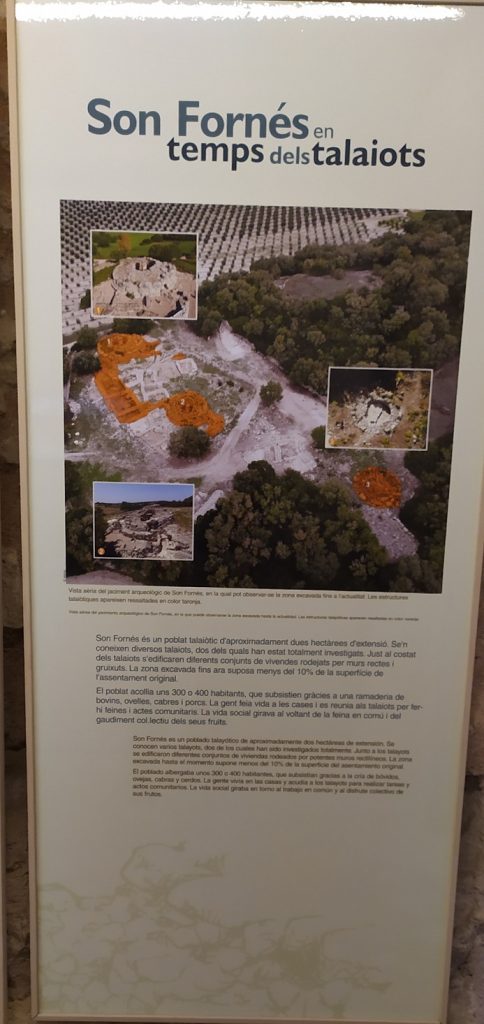

10. Son Fornés in Talayotic times

Son Fornés is a Talayotic settlement of approximately 2 hectares. There are three known talayots, of which two have been completely examined. Together with the talayots, there were various groups of houses, surrounded by strong rectilinear walls. The area excavated so far is considered to be less than 10% of the original settlement. The settlement had a population of 300 or 400 inhabitants, who bred cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. The people lived in the houses and used the talayots for carrying out community tasks and rites. Social life revolved around communal work and the collective enjoyment of its produce.

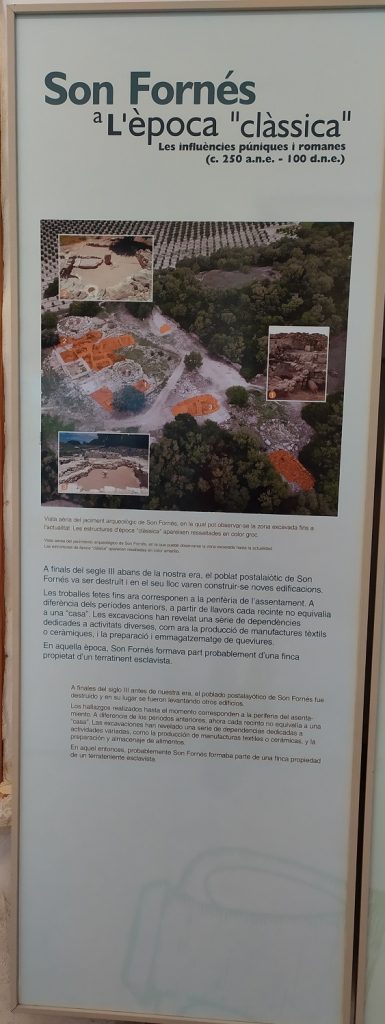

Aereal view of the archaeological site of Son Fornés, which shows the area excavated so far. The Talayotic structures are highlighted in orange.

11. Daily life in the settlement

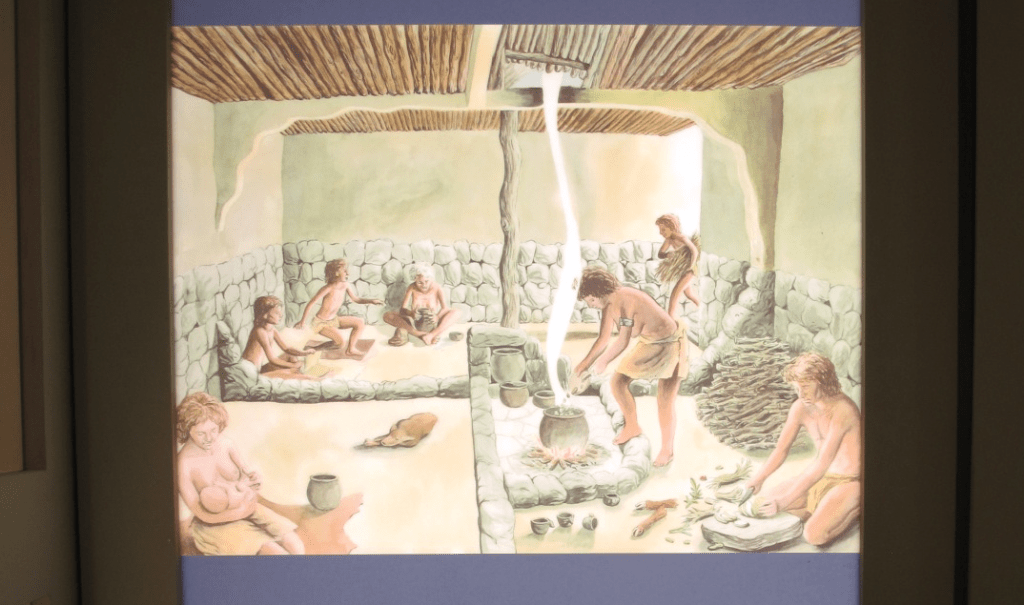

Around 850 before Christian Era, a community searched for a place to live in the Pla de Mallorca, a hardly populated region up to those times located in the center of the island. They chose a small hill and laid the foundations of what is now known as Son Fornés. The Talayotic community which founded Son Fornés inhabited this place for 300 years. It was organized around relatively self-sufficient domestic units of between 5 and 10 people, probably related. All of these domestic units had the necessary tools for preparing and serving food, making pottery, and sewing clothes. Moreover, they took charge of caring for the children.

Solidarity was quite noticeable: no domestic unit took advantage of the others’ work.

12. Aerial photographs of Son Fornés

13. Let’s get into the Talayotic House 1

14. 40 m2, 7 people, 25 objects

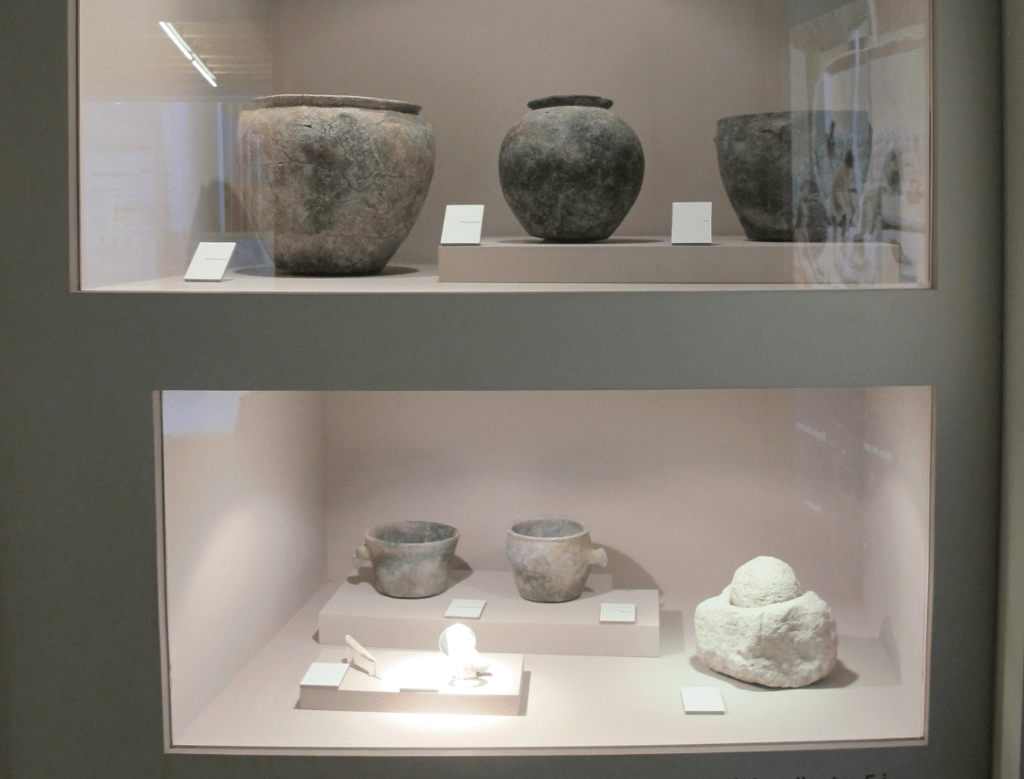

Using this small collection of objects, a Talayotic domestic unit of between 5 and 10 members could provide for the majority of its daily basic requirements.

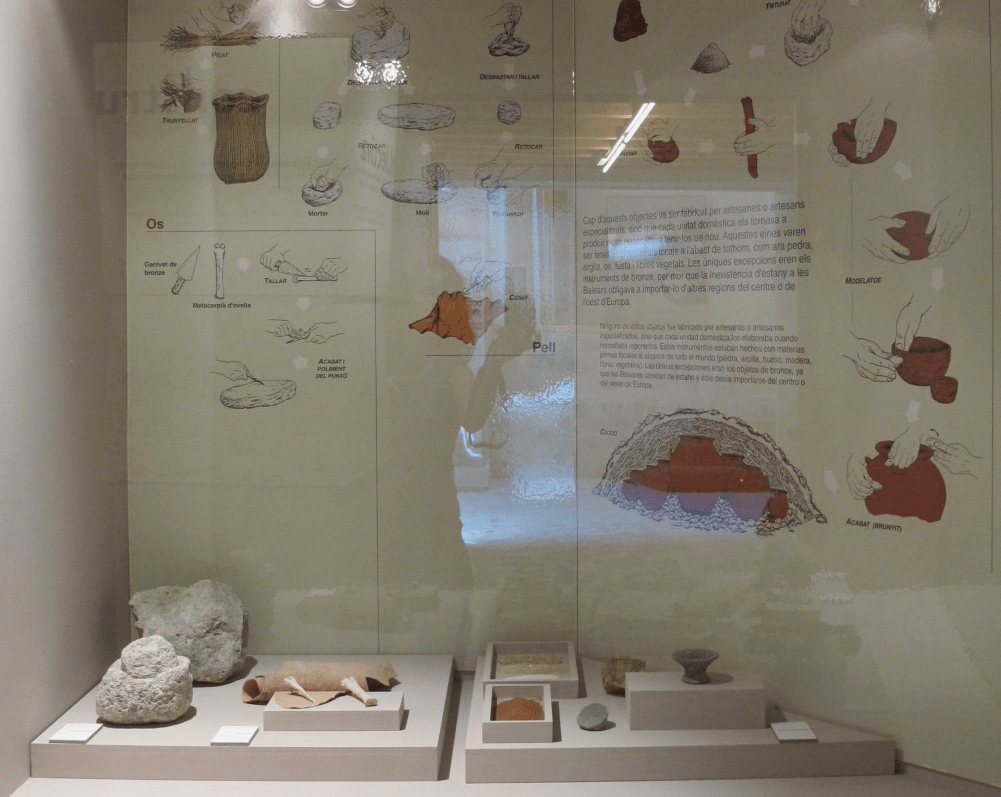

15. Home – made

None of these objects was made by specialist artisans, rather, each domestic unit produced them when they needed to replace the old ones. These instruments were made of materials which are locally and freely available (stone, clay, bone, wood, vegetable fibre). The only exceptions are bronze instruments, since the Balearic Islands lack tin, and had to import it from Central and Western Europe.

Drawings: Basketry – Stone – Bone – Leather – Pottery

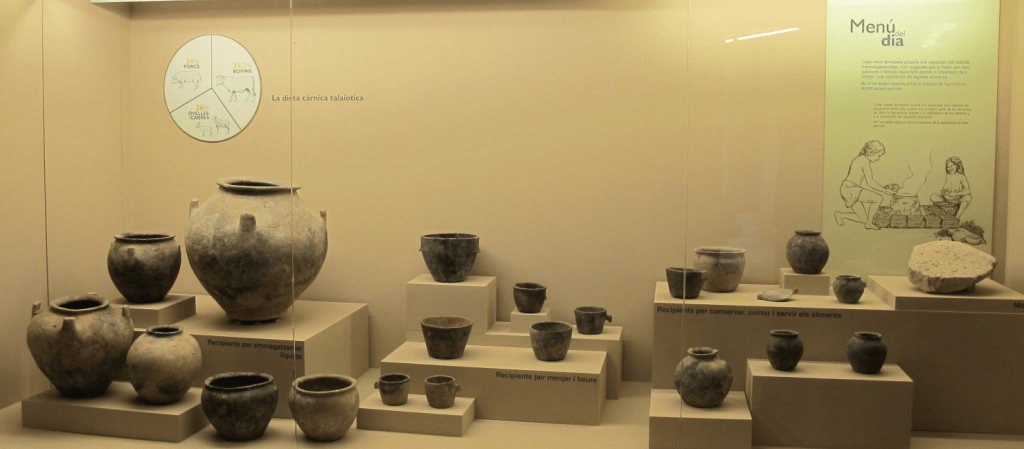

16. Daily menu

Each domestic unit had a very reduced capacity for storing food. This suggests that the main part of the foodstuff was obtained daily from livestock and gathering of wild vegetables. There are no certain data on the use of agricultural practices from this period.

Graphic: Meat in Talayotic Diet

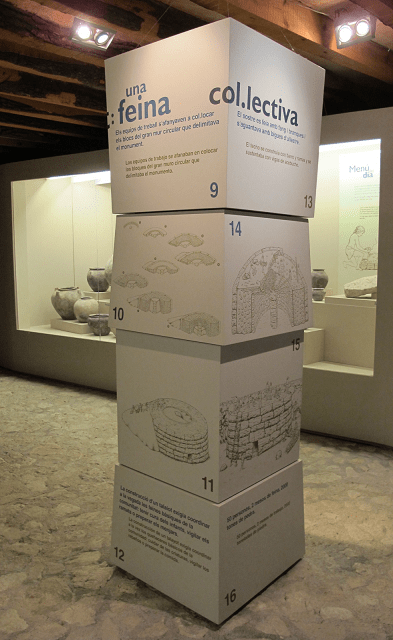

17. Building up a talayot: a collective task

1. Nearby outcrops of calcareous rocks provided the raw materials for the construction of the talayots.

4. Some blocks weighed more than 9 tones.

5. Quarrying and moving of blocks required the collaboration of many people.

8. Simple tools were used, such as ropes, wedges and wooden levers.

9. The work teams labored at placing the blocks of the large circular wall which delimited the monument.

12. Building of a talayot required coordinating the basic tasks of the community: looking after the children, watching over the livestock and preparing the meal.

13. The roof was built with mud and branches, supported on olivewood beams.

16. 50 people, 2 months of work, 2,000 tones of stone

18. The talayot: a space with multiple uses

The talayots did not have a single function, but several. Moreover, not all of them were used for the same purposes despite having a similar shape.

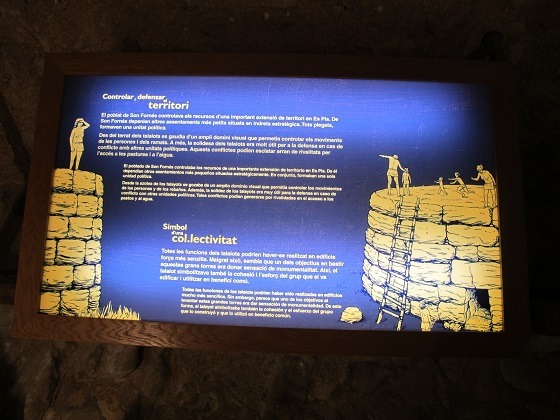

19. Territorial defense and control

Son Fornés controlled the resources of an important stretch of Es Pla. Other smaller strategically situated settlements depended on it. Together they formed a single political unit. The roofs of talayots provided a broad view over the surrounding countryside, allowing the community to control movements of people and herds. Moreover, the solidity of talayots was very useful for defense in conflicts with other political groups. Such conflicts might have happened due to rivalry for access to grazing lands and water.

Symbol of a social group

A ll of the functions of a talayot could have been carried out in much smaller buildings. However, it seems that one of the aims in building these immense towers was to give a sense of monumentality. In this way, talayots also symbolized the cohesion and efforts of the groups which constructed them, and used them as common goods.

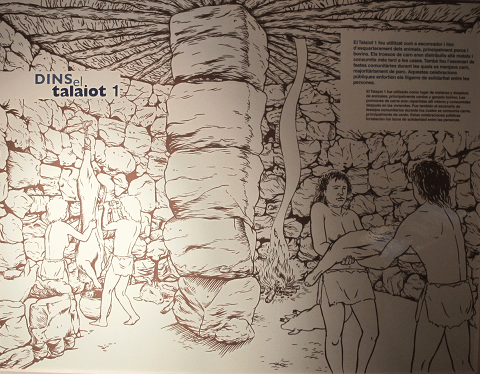

20. Inside Talayot 1

Talayot 1 was used as a place to slaughter and butcher animals, mainly pigs and cattle. Portions of meat were distributed there and eaten afterwards in the houses. It was also the site of communal festivals, during which meat, mostly pork, was eaten. These public celebrations reinforced the ties of solidarity between the members of the community

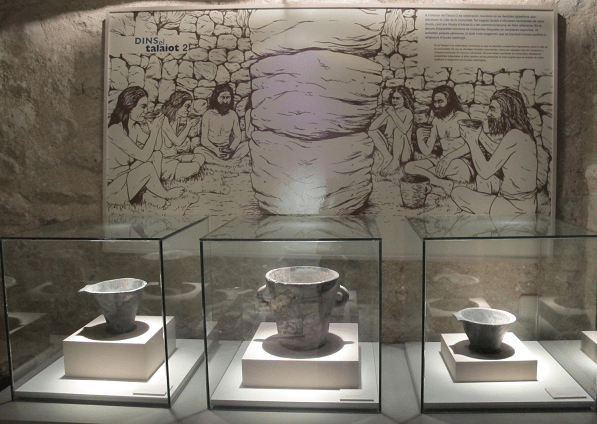

21. Inside Talayot 2

In Talayot 2 meetings were held, to decide on important matters for the community. Perhaps ceremonies were also celebrated, such as initiation rites or commemorations of important events. During these meetings, drinks were taken from special bowls. Few people attended the meetings, which suggests that they dealt with political and religious activities with limited access.

22.

A few centuries after its start the Talayotic society entered a period of crisis. Mechanisms of solidarity and mutual support were broken and certain social groups began to control labor relation, and access to critical territory’s resources. A phase of social conflict began, which affected the Balearic Islands as a whole, and life in Son Fornés became impossible. Finally the settlement was destroyed and abandoned.

Post-Talayotic Phase (550 – 250 before Christian Era)

23. After the Talayots: The beginnings of inequality. Postalayotic Phase, Classic Phase and Late Medieval Phase (banner)

24. A Time of conflicts

Conflicts for control of the Mediterranean

During the 5th, 4th and 3rd centuries BCE, the Mediterranean lived through an age of great upheavals due to the expansionist policies of some of the great states, such as Carthage, Rome and Macedonia. This is reflected in the large number of wars which bloodied the Mediterranean in this period, and which finally ended up in the consolidation of Rome as the hegemonic power.

Although Mallorca and Menorca remained at the edge of the principal theatres of operations, many of their inhabitants participated directly in numerous military campaigns, enrolled as mercenaries in the Carthaginian armies.

Post-Talayotic Mallorca. Territorial control

During Post-Talayotic period most of previous settlements were reoccupied or remodeled. Talayots lost their original uses and many of them were in complete ruins. Houses were rebuilt and rearranged without following any particular pattern.

The island territory was divided into political units controlled by dominant social groups. The presence of weapons and of fortified settlements, some of them even with towers and bastions, suggests that the powerful protected their own privileges by force, and that, moreover, there were occasional rivalries among them for territorial control.

This does not deny the existence of political alliances which stabilized each political unit and promoted large exchange networks and widespread agreements about military participation in external campaigns.

T he so-called “sanctuaries” were widely used, perhaps with a ceremonial function similar to that of the famous Menorcan “taulas”.

We know quite a bit about Post-Talayotic funerary rites, which were carried out mainly in natural caves as well as in in other artificially excavated cavities.

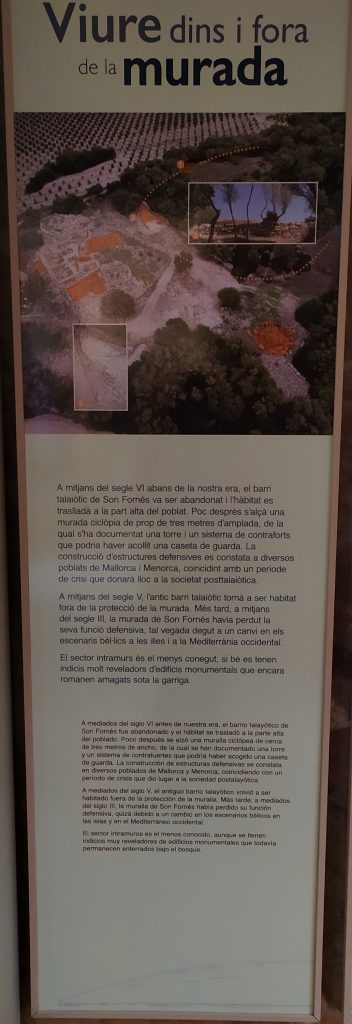

25. Living inside and outside the town walls

Aerial view of Son Fornés archaeological site showing the area excavated up to now. The Postalayotic structures are highlighted in orange.

The Talaiotic village was abandoned by the middle of the 6th century before the Christian era and the settlement moved to the nearby upper fields. A 3 meter thick Cyclopean rampart was then built. Excavations have explored so far two stretches of its somewhat circular layout and have brought to light a tower and a series of buttresses next to what it looks like a checkpoint. Other contemporary settlements both in Mallorca and Menorca experienced the same fortification process. This period of crises involved the onset of a new society that we actually refer to as Postalaiotic.

The new village was fortified but other constructions were also built on the ruins of the old Talaiotic district. Some of them did use already existing walls, while some others were completely brand new.

The Postalayotic community lasted until the 3rd century BCE, when a combination of inner and outer pressures fostered further social changes. The rampart became useless and was finally abandoned just 150 years after its construction.

Only new excavations will allow to discover the village layout as well as the relationship between the suburb inside the town walls and the houses and sanctuaries that stood outside their protection.

26 + 27. Let’s get into the Post-Talayotic House 1

A Post-Talayotic domestic unit used many more daily objects than in the Talayotic period, despite the fact that both contained similar numbers of members.

The great storage capacity of each dwelling was due to the increased food production, now based on agriculture and livestock.

28. Domestic furnishings

The majority of the objects were made from locally available raw materials, (clay, stone, wood). However, there continued to be an external dependency with respect to bronze, and possibly iron, as well as a progressive increase in the use and consumption of exotic materials, such as glass beads and Ibizan wine.

It is possible that a part of the products obtained by the domestic units which we know from Son Fornés were used to maintain the members of the ruling group of Post-Talayotic society.

It may be that some of the powerful individuals lived in other, still unexplored, neighborhoods in Son Fornés itself, while others lived in much more extensive fortified settlements.

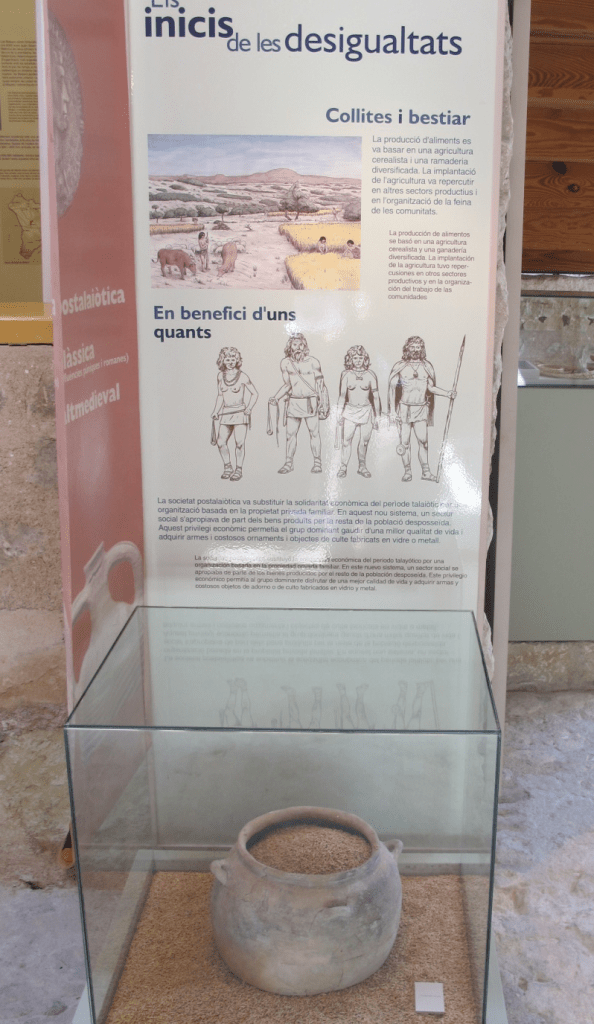

29. The beginnings of inequality

Harvests and livestock

The production of foodstuffs derived from a cereal-based agriculture, and a diversified livestock production. The introduction of agriculture affected other productive sectors as well as the organization of community work.

Benefits to the few

Post-Talayotic society replaced the economic solidarity of the Talayotic period with a form of organization based on family private property. In this new system, one social sector appropriated part of the goods produced by the rest of the population, which was dispossessed. This economic privilege allowed a dominant group to enjoy a higher quality of life, and to acquire more weapons, costly jewelry and cult items, made from glass and metal.

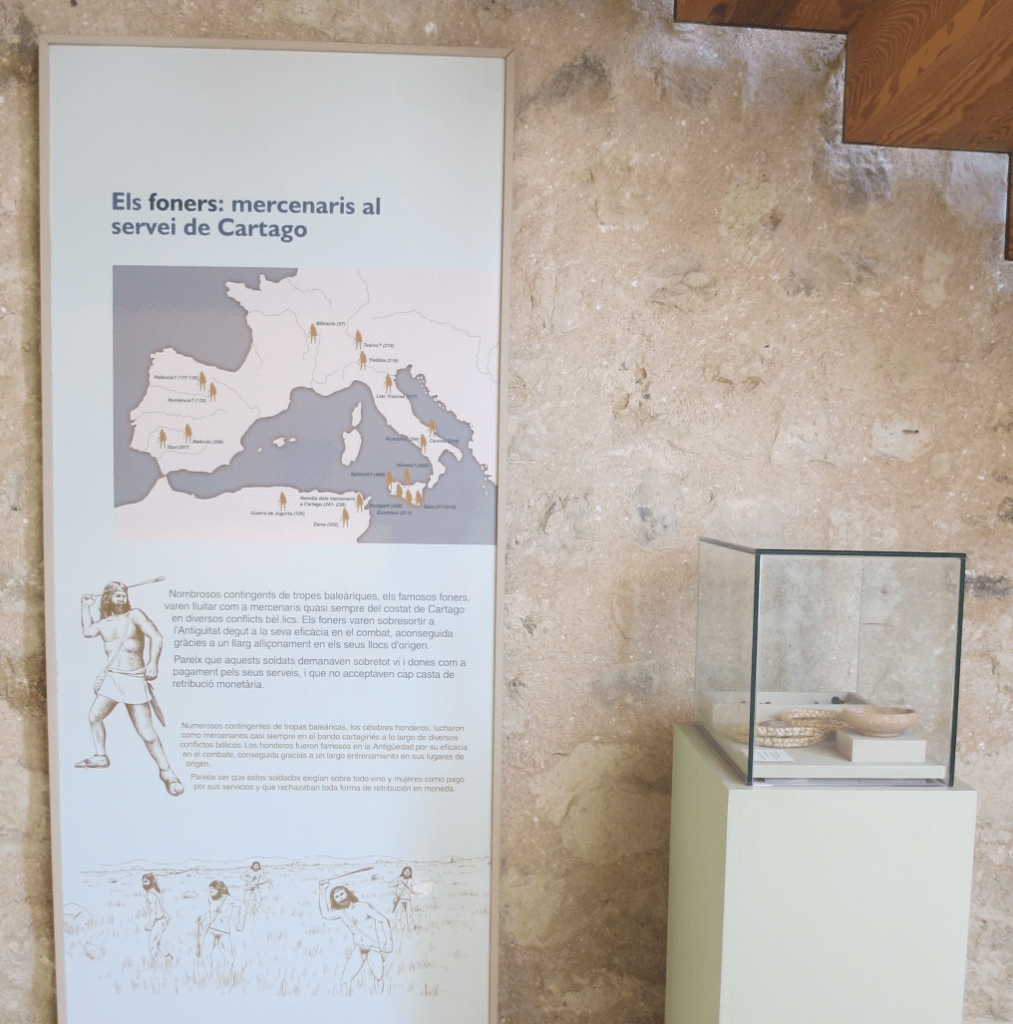

30. The slingshot warriors: mercenaries employed by Carthage

Numerous contingents of Balearic troops, the celebrated “honderos” (slingers), fought as mercenaries in Carthaginian troops, in the many wars unleashed in Sicily and the Italian peninsula. The “honderos” were famous in the Ancient World for their efficiency in combat, achieved thanks to a thorough training in their homeland. It seems that these soldiers asked for wine and women in return for their services rejecting all monetary reward.

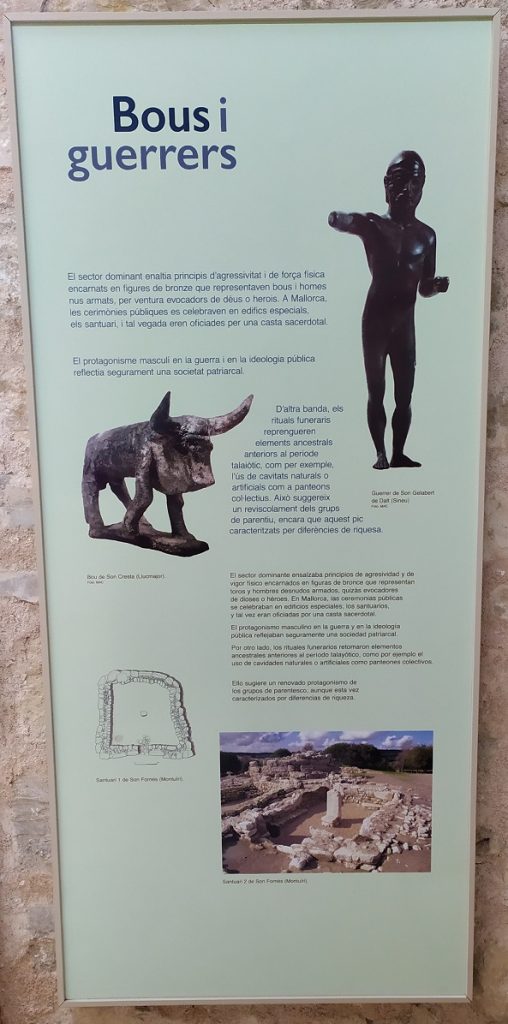

31. Bulls and warriors

The dominant sector extolled principles of aggression and physical vigor, embodied in bronze figures representing bulls and naked armed men, perhaps evoking gods or heroes. In Mallorca, public ceremonies were celebrated in special buildings, the so-called sanctuaries, perhaps overseen by a priestly caste.

Male protagonism in war and in public ideology surely reflected a patriarchal society.

On the other hand, funerary rites evoked ancestral elements previous to the Talayotic period, such as, for example, the use of natural or artificial caves as collective pantheons. This suggests a renewed protagonism on the part of the kinship groups, although this time characterized by differences in wealth.

Pictures: Bronze bull from Son Cresta (Llucmajor). Photo: MAC. Bronze warrior from Son Gelabert (Sineu). Photo: MAC. Son Fornés Sanctuary 2 (right). Ground plans of Son Fornés sanctuary 1 (left).

Classic Phase: 250 BCE – 100 CE (Christian Era)

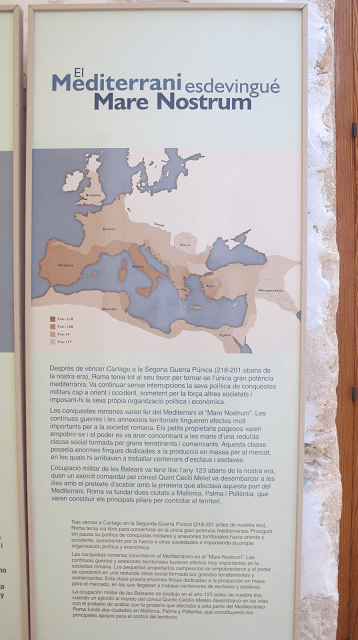

32. The Mediterranean became the Mare Nostrum

After conquering Carthage in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), Rome was free to become the only major Mediterranean power. Rome persecuted its policy of conquest and territorial annexation without pause to the East and West, subjecting other societies by force, and imposing its own political and economic organization.

The Roman conquests transformed the Mediterranean into the “Mare Nostrum”. The continuous wars and territorial annexations had extremely important effects on Roman society. Small peasant landowners grew poorer, and power ended up concentrated in the hands of a small social class made up of large landowners and merchants. This class possessed enormous farms which they dedicated to mass production for the market, in which hundreds of slaves came to work .

The military occupation of the Balearic Islands took place in 123 BCE, when an army commanded by consul Quintus Cecilius Metelus disembarked in the islands with the excuse of putting an end to the piracy which affected this part of the Mediterranean. Rome founded two cities in Mallorca, Palma and Pollentia, which became the two main supports for her territorial control.

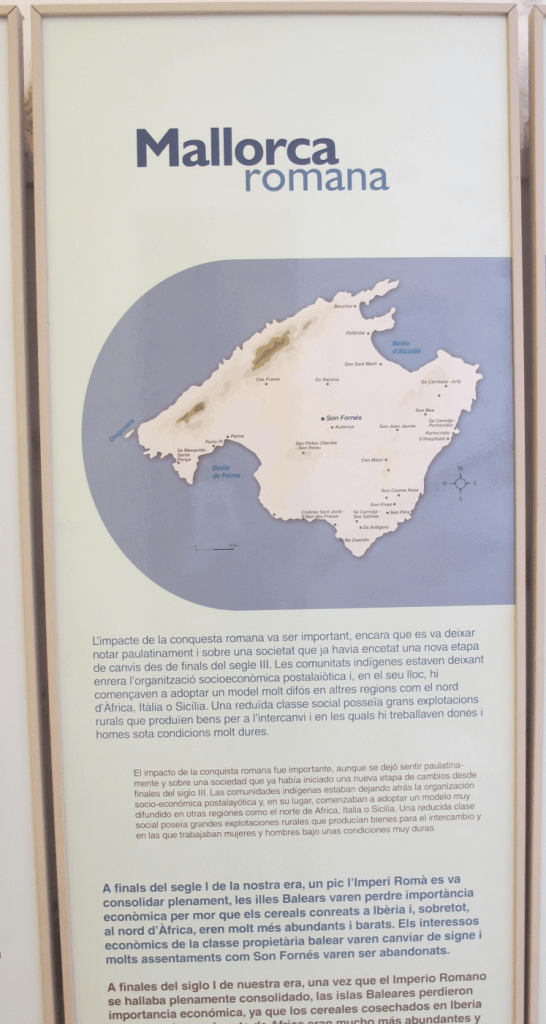

33. Mallorca under Rome

The impact of the Roman conquest was important, although it was felt only gradually, and in a society which had already begun to undergo a new phase of change from the beginning of the 3rd century BCE. The indigenous communities had left Post-Talayotic socio-economic organization behind. They had begun to adopt a model widely used in other regions such as the North of Africa, Italy and Sicily. A small social class possessed large rural landholdings, which produced goods for exchange by means of women and men working in extremely hard conditions.

At the end of the 1st century BCE, once the Roman Empire had been fully consolidated, the Balearic Islands lost economic importance, since cereals harvested in Iberia and, specially, North Africa, were much cheaper and more abundant. The economic interests of the Balearic property owning class changed direction, and many settlements such as Son Fornés were abandoned.

34. Son Fornés during the Classic Period: Punic and Roman influences

Towards the end of the 3rd century BCE, the Post-Talayotic settlement of Son Fornés was destroyed, and other buildings were constructed among its ruins.

The findings up to the present correspond to the outskirts of the settlement. In contrast with previous periods, there were no spaces which could be called “houses” properly. Excavations reveal a series of structures used for varied activities, such as the production of manufactured textiles or ceramics and the preparation and storage of foodstuffs.

At that time, Son Fornés was probably part of a large farm belonging to a slave-owning landlord.

35. Imported ceramics

In spite of the arrival of ever more high-quality ceramics from Italy, Iberia and Ibiza, Roman domination didn’t stifle the ancient tradition of making pots without a wheel. This continuity indicates the survival of traditional technologies.

Local ceramics

Some locally-produced pots imitated Roman wheel-produced pottery.

36. A long journey

From the beginnings of the 2nd century onwards, larger and larger quantities of amphorae reached Son Fornés, as a consequence of the integration of the Balearic Islands into Roman economic structure.

The amphorae were mass-produced ceramic containers, which tended to be used for foodstuffs (oil, wine, preserved fish) destined for exchange. The most used means of transport was the boat, which allowed the shipment of large cargoes over long distances, and with relative speed.

The majority of the amphorae found in Son Fornés contained wine. It is interesting to point out that imported bowls for drinking wine also often arrived with these amphorae.

Legend

Origins of the amphorae found in Son Fornés.

37. … and money appeared

One of the consequences of the Roman domination was the introduction of money as a means for regulating transactions and collecting tribute. As a result, the traditional forms of exchange based on barter began to fall into crisis.

New technologies

In this period, the use of iron tools specialized for concrete uses such as pruning and harvesting, became generalized. These tools allowed an increase in agricultural production. The raw materials and, perhaps, the instruments themselves, must have been acquired through exchange.

This type of mill was possibly invented in Sicily in the 4th century BCE, and constitutes an extremely advanced tool for that time. Its introduction to the island implies a great increase in productivity, since it could mill in just 5 minutes the same amount of grain as could be milled in an hour with the old flat Post-Talayotic mills.

The bones speak

The new production relationships established even before the Roman conquest, resulted in extremely hard conditions for the majority of the population, which was exploited by the property owning class.

This is testified to by the remains of 2 women and the child of one of them, buried humbly in the outskirts of Son Fornés in the 2nd century BCE. One of the women suffered from malnutrition, illnesses, broken and deformed bones, as a result of carrying out heavy labour. She finally died in her 30s. The second woman died younger, at about 22, perhaps during childbirth. Her child also died, and was buried with its mother.

Late Medieval Phase (Vth-VIth centuries Christian Era)

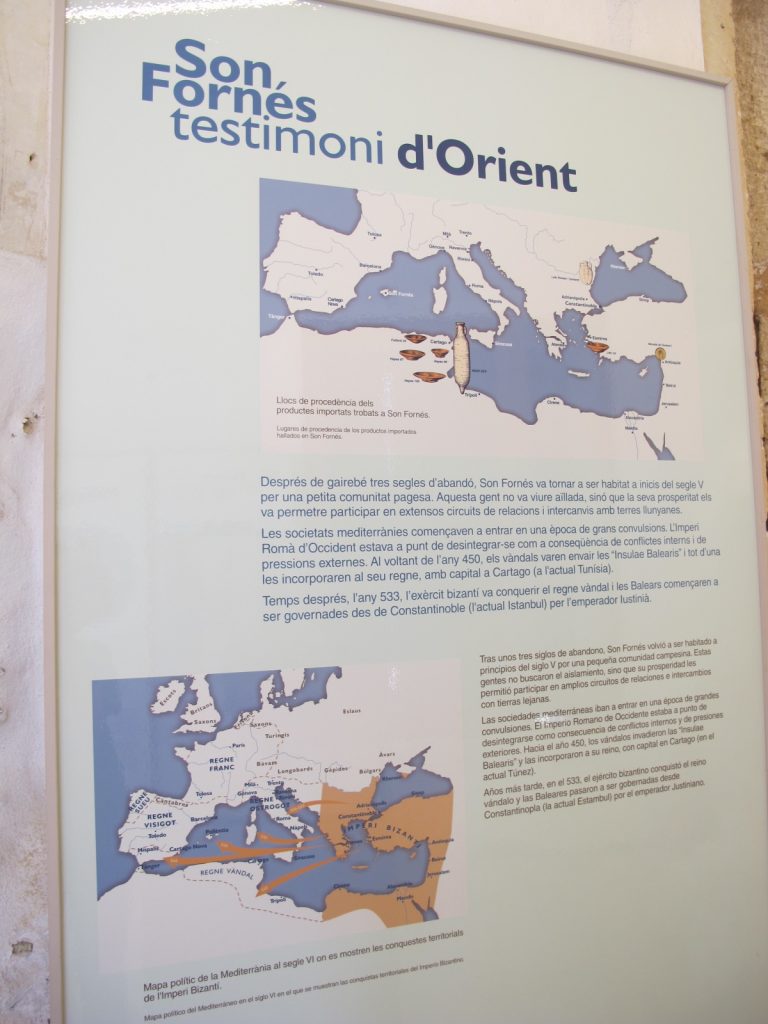

38. Son Fornés, witness of the East

After some 3 centuries of abandonment, Son Fornés was once again inhabited towards the beginnings of the 5th century AD by a small peasant community. Nevertheless, these people were not seeking isolation in a rapidly changing world, but rather their prosperity allowed them to participate in wide circuits of exchange and relations with distant lands.

At around that time, the Mediterranean societies were undergoing a period of great upheavals. The Western Roman Empire was at the point of disintegration, as a consequence of internal conflicts and external pressures. Around 450, the Vandals invaded the “Insulae Balearis”, incorporating them into their kingdom, with its capital in Carthage (now called Tunis).

Some years later, around 534, the Byzantine army conquered the Vandal kingdom, and the government of the Baleares passed to Constantinople (Istanbul), under the emperor Justinian.

Little is known about what happened from the 7th century onwards, when the Byzantine empire lost a large part of its most Westerly possessions. Towards 903, the Balearic islands were integrated into the Emirat of Al-Andalus.

Upper Map: Origins of the imported products found in Son Fornés.

Lower Map: Political map of the Mediterranean during the 6th century, showing the territories conquered by the Byzantine Empire

39. Christ was engendered by Mary

As well as being used for commercial purposes, this amphora transported ideas. In this age, Christianity was a doctrine agitated by many theological debates, which gave cover to deeper political and economic conflicts.

The text in Greek affirms the human nature of Jesus Christ, having been engendered by a woman, Mary. This message may have been written by a follower of Nestorianism, a doctrine which appeared at the beginning of the 5th century in the Eastern Roman Empire, and which was qualified as heresy at the Council of Ephesus (431). According to its beliefs, Christ united two different personae, one divine, the other human. In this sense, Mary was only the mother of a man, not of God.

In the period in which the amphora circulated with its message, Nestorianism and its derivatives, were persecuted for contradicting Christian orthodoxy (two natures, and only one Persona in Christ), underwritten by the power of the emperor.

Photo: Detail of a mosaic from the palace of the emperor Justinian in which can be seen an amphora of the same type as the one found in Son Fornés

40. The end of our story

Towards 624 the Byzantine Empire lost its territories in the Iberian Peninsula, and in 689 those in the North of Africa, and as such, the economic ties between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean were temporarily interrupted. It is impossible to be certain whether the Balearic Islands continued to form a part of the Byzantine Empire, although it is possible that during the two centuries that followed they maintained their independence, and developed a social organization which remains unknown.

Finally, when the Emirat of Cordoba annexed the Balearic Islands in 903, Son Fornés was practically uninhabited.